Puerperal Mania in Four Stages, 1858

Alienists in the 1800s believed that most madness stemmed from a physical cause that then created mental symptoms. Women, because they were physically weaker, were more prone to madness and had to be sheltered or restricted from many stressful situations. Unfortunately, motherhood–woman’s highest calling in the minds of many and almost unavoidable for married women–could be an “exciting cause” of insanity because of its physical strain on the body.

Madness associated with pregnancy fell under the general term “puerperal insanity” and was further divided into three categories: gestation, lactation, or parturition (childbirth). The insanity of gestation tended to be rare and usually manifested during first pregnancies; its symptoms included melancholia, suicidal thoughts, and apathy. It was generally cured upon the birth of the child. The insanity of lactation had similar symptoms but tended to occur during subsequent pregnancies. This type could be more serious and end with complete dementia, though it typically resolved within a few months. The insanity of parturition was quite different–women manifested manic symptoms rather than melancholy. These mothers talked incessantly, couldn’t sleep, rejected their children or husbands, cursed, and otherwise dismayed and dumbfounded the males in their lives.

Admission Statistics, Including Puerperal Insanity, courtesy Missouri State Archive

Women were often committed to asylums during these problematic episodes. Fortunately, physicians generally treated puerperal insanity with–for the time period–restraint and common sense: rest, food, purging, and sedation. Depending upon the symptoms, patients might also be closely watched or confined to prevent them harming themselves.

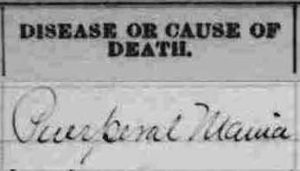

1890 Death Record from Michigan

Though the diagnosis of puerperal insanity probably stemmed largely from the male gender-bias that expected women to be gentle, subdued, and “ladylike” at all times, male physicians did recognize that in most cases, the condition would be short-lived. Rather than being confined in an asylum for years, most women recovered in six months or so and resumed a normal life.