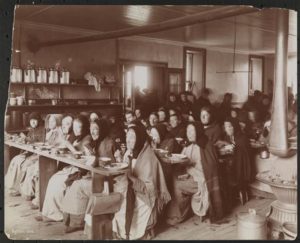

Commercial Hospital Began Ambulance Service in 1865, courtesy National Library of Medicine

Ohio became a state in 1803 and quickly realized the need for an insane asylum; its initial institution was established as The Commercial Hospital and Lunatic Asylum of Ohio in Cincinnati. Built without delay, in January, 1824, the hospital’s trustees were able to put a notice in the Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Gazette: “. . . the undersigned trustees hereby give notice . . . that they are prepared to receive idiots, lunatics and insane persons.”

Though it was a gentle enough invitation, these unprotected guests of the state may not have enjoyed their stay. Built before reformer Dorothea Dix’s campaign to treat the mentally ill with kindness and understanding, the asylum was as much a prison as a place of healing. In 1831, the state legislature even asked the question as to “whether the cells and apartments of the lunatic asylum are sufficiently separated from each other by thick walls to prevent the inmates from communicating with each other.” Was solitary confinement their goal?

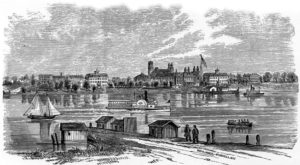

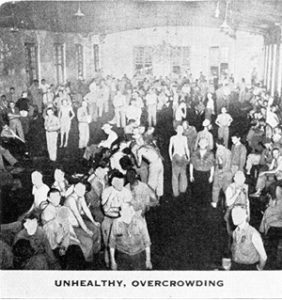

Longview Asylum, 1860

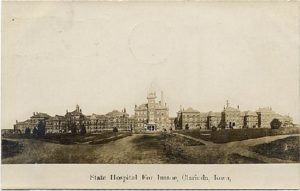

Though stumbling a bit at inception, the hospital was the starting point for an orphan asylum, the city infirmary, the Cincinnati Hospital, and Longview Asylum. A description (from 1916) of patients’ rooms at Longview shows a dramatic upswing in comfort from what must have been dismal quarters at the original Commercial Hospital:

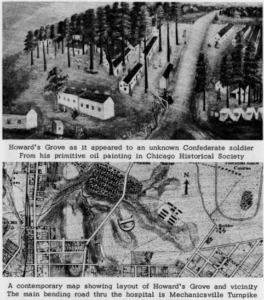

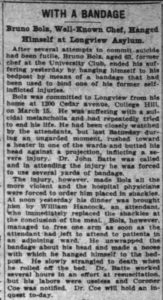

1910 Article Shows That Asylum Was Fallible

“The walls are covered with photographs of the best pictures of the world . . . . Everywhere throughout the house are inlaid tables and unusual pieces of fancy furniture, fancy needlework, flowers, singing birds, bric-a-brac, etc. which is seldom roughly handled or destroyed by patients. In each ward is a tastily furnished cozy corner, fitted up with book shelves, easy chairs, etc., where patients who will not abuse the privilege are allowed.”