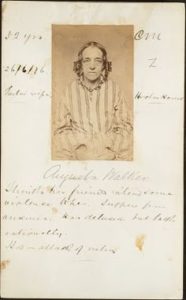

This Delusional Woman Believed Her Friends Wanted to Hurt Her

Though many alienists (a term for early psychiatrists) felt perfectly competent to treat insanity, few felt that they could actually define it. In his book, A Treatise on Insanity in its Medical Relations (1883), Dr. William Hammond demonstrated the difficult of defining insanity by citing various experts:

“According to Hoffbauer, an individual is insane when the understanding is diverted . . . when he is powerless to avail himself of his intellectual facilities, or to make known his wishes in a suitable manner.” However, Hammond pointed out, this definition would include conditions like “apoplexy and concussion and compression of the brain.”

“The late Professor Gilman . . . declared that ‘insanity is a disease of the brain by which the freedom of the will is impaired.'” As with the previous definition, however, Hammond declared that “this definition neither covers the subject nor excludes other diseases.”

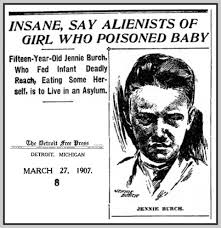

Insanity Could Lead to Unthinkable Crimes

Several alienists Hammond quoted declined to define insanity at all, saying that no definition in any kind of general terms would be useful. Even common manifestations of insanity such as illusions, hallucinations, and delusions could not definitively diagnose it, since there were reasons why these conditions might occur whether a person was insane or not.

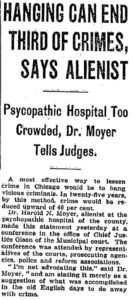

Alienists Did Not Necessarily Believe Insanity Caused All or Most Crime (January 19, 1919 Issue of the Chicago Tribune)

One of the issues surrounding the diagnosis of insanity through the ages is that the condition can’t really be defined the way a case of measles or a broken leg can be. Culture, custom, expectations, and so on constantly refine what is acceptable behavior or what will be tolerated through the ages and across cultures.

That leaves the question: What is insanity?