Columbus Asylum for the Insane

Asylum superintendents could be focal points of animosity from both patients and the public (see last two posts), but patients were really the ones who suffered most from violence. They were at the mercy of staff, and if their attendants were cruel or took a dislike to them, they were almost helpless.

A Boston Post article from November 12, 1878 entitled “FIENDISH CRUELTY” described a situation of systematic cruelty at the Columbus (Ohio) Asylum for the Insane that is hard to imagine. An investigation had discovered that for the past thirteen months, female patients had been victimized by a type of discipline called “ducking.”

When a patient wouldn’t immediately obey an order from her, an experienced attendant in the chronic insane ward named only as Mrs. Brown, would “rush the offending victim to the bath room, where she was stripped of her clothing and thrown into the water. The unfortunate patient’s head was forced under the water until the poor creature was nearly strangled, and then her head was raised for a moment that she might recover,” the paper reported.

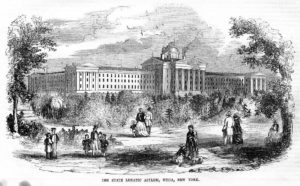

Hydrotherapy Was a Well Established Method of Treatment for the Insane

The process was repeated until the victim was so exhausted and terrorized that she would promise to obey the attendant at all times. Mrs. Brown enlisted her fellow attendants to do likewise, and they ran the ward with an iron hand. The Boston Post reported that the patients were so afraid that “the slightest motion of the finger by an attendant met with abject obedience.” But the matter didn’t end there, the paper continued. “A compact was made with the attendants from other wards and a secret alliance formed . . . . The physicians were hoodwinked.”

Finally, one of the female attendants involved was discharged, and she suspected that Mrs. Brown was involved in the dismissal. The attendant brought all the abuse forward as charges against Mrs. Brown, and spurred an investigation. Evidence/testimony proved that at least ten female attendants had “ducked” patients this way.

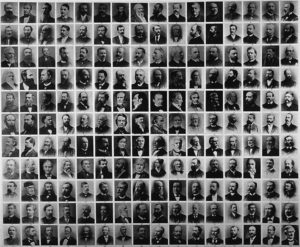

Nurses From Northern Hospital for the Insane, 1890s, courtesy Oshkosh Public Museum

Though they were immediately discharged, who knows how many patients suffered at their hands before their actions were discovered? At the time of the article’s appearance, the investigation had just started.