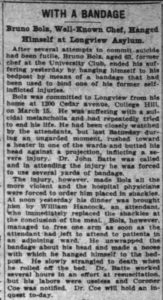

Sympathetic Writer Tells Anna’s Story

Newspaper articles often reflect society’s view of an issue, or they can offer a view that the writer wants the public to consider. A compassionate article in the June 9, 1905 issue of the Evening World (NY, NY) was the latter type.

A woman named Anna Valentina had killed her long-time partner’s mistress under sorrowful circumstances and awaited hanging in Hackensack, NJ. Anna had fallen in love with a fellow Italian named Mike Calluel many years earlier, and he seemed by all accounts to be hard, cruel, and selfish. He used Anna relentlessly.

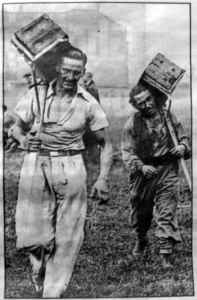

For ten years–always with the promise of marriage before her–Anna worked physical jobs all day (including construction), and kept house, cooked, and cleaned for Mike as well. She eventually bought a piece of land with the money she she earned, believing the purchase was one step closer to marriage. Unfortunately, she gave the property to her lover. Mike Calluel took up with a young woman named Rosa Salza and threw Anna out of the house she had bought and physically helped build for him.

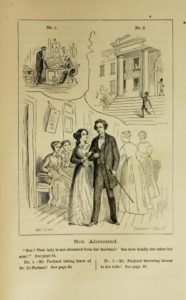

Anna Carried Hods of Brick Like These in Her Daily Work

Mike and his new lover were evidently soul mates–Rosa simply laughed at Anna’s plight. The spurned woman held out hopes that Mike would finally return to her, so she remained in the area and frequently saw Rosa in the house she had lost to her. Rosa insulted and provoked Anna every time she saw her, and one day either spitefully called Anna in to see her or goaded Anna into coming into the house. One of Anna’s greatest tragedies was the inability to have children, and Rosa now had twins. Rosa both taunted her with the twins and mocked Anna’s worn-out face and figure until Anna finally went mad.

Anna Valentina in a December 20, 1905 Issue of the Evening World

To underscore how deliberate Rosa’s behavior was, the paper reported that Rosa expected Anna to be upset and had kept a knife behind her back. Unfortunately for her, Anna was still strong from all those years of work, and wrenched the knife from Rosa and stabbed her to death.

My next post will discuss Anna’s fate.