Kansas Pioneers Struggled Constantly

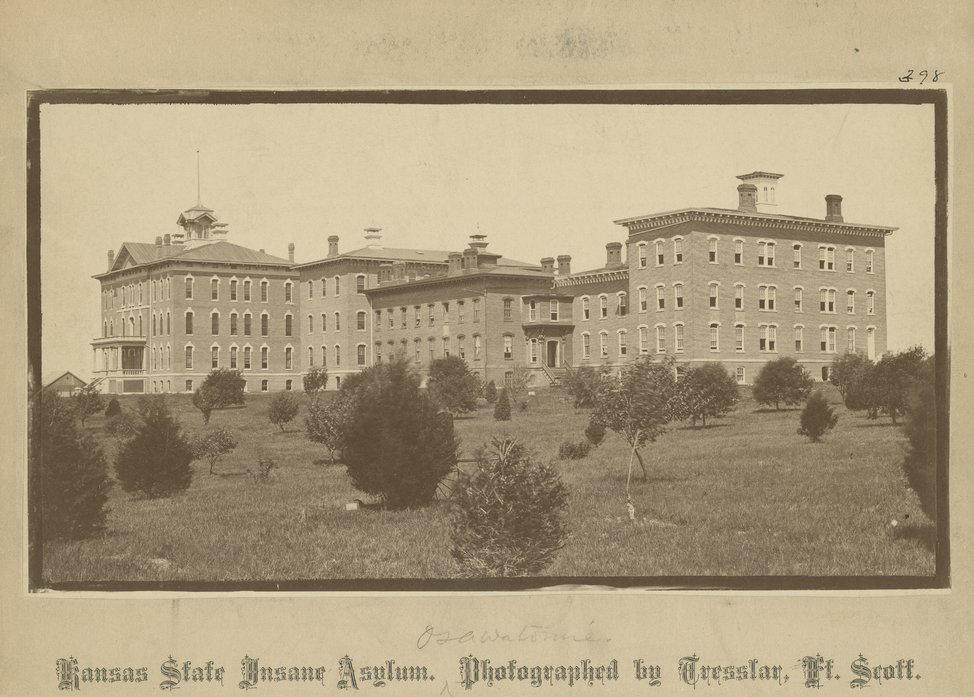

As pioneers pushed westward, mental health issues went with them or developed once settled (see last post). Kansas established its first insane asylum in 1863, which opened in 1866 and was known as the Kansas State Insane Asylum and later as Osawatomie State Hospital. Three trustees managed it until 1873, when a six-member board of trustees appointed by the governor took over. Trustees were paid three dollars a day (about $62 today) and mileage, as was a separate citizen committee which visited the institution at least twice a year.

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.

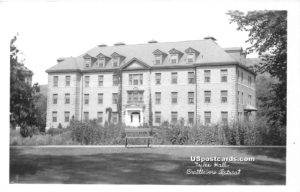

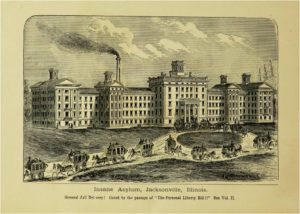

Osawatomie State Hospital’s Old Main Building, Constructed in 1869

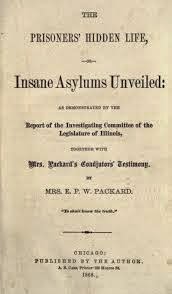

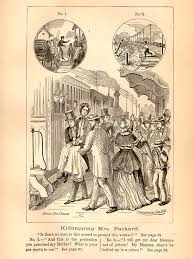

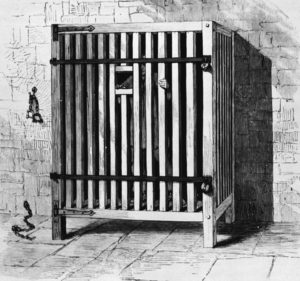

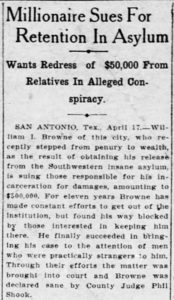

Comprehensive legislation relating to the asylum in 1870 introduced another way of admission. This method did not inquire into a person’s insanity. Instead, a doctor could certify that he believed a patient was insane–and that certification along with a bond for maintenance signed by any individual and approved under a probate court–was enough to admit someone to the asylum. This sort of involuntary commitment could be made only at private expense, so indigent citizens were relatively safe from it.

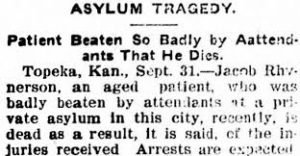

Not so for patients whose absence may have benefited an unscrupulous relative or guardian in some way. We can certainly speculate about the number of inconvenient spouses, wayward children, and other undesirable relatives who resided in this Kansas asylum.