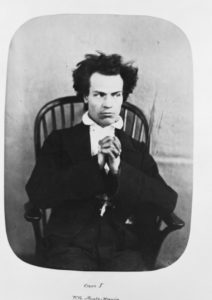

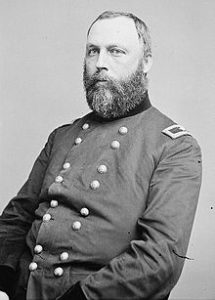

Former Surgeon-General Dr. William A. Hammond

After going through old medical texts about insanity, researchers might be tempted to think that families and doctors believed any odd behavior was a manifestation of insanity. There is a kernel of truth to that, since insanity is usually based on a violation of societal norms. Unfortunately for many asylum patients, their families often took that viewpoint a step further and considered a person insane when they merely disagreed with his or her conduct or beliefs. Dr. William A. Hammond, in his influential book, Treatise on Insanity (published 1883), did try to distinguish between insanity and mere quirkiness.

Hammond began his discussion of eccentricity with the example of a man who had left his considerable fortune to the “funding of a hospital for sick and ownerless dogs.” In this case–and particularly in this era–the man’s wish would be puzzling to say the least. However, Hammond says that if the man had endured circumstances in life that “weakened his confidence in human nature,” his will would be much more understandable. In his eyes, dogs were “the most faithful creatures I have ever met, and the only ones if which I have confidence.” Hammond said firmly that such a man was not insane; there was a rational motive for his conduct.

Nikola Tesla Could Not Stand Jewelry, Especially Pearls

Hammond regarded this form of eccentricity, in which the person “sets himself up above the level of the world” and marks out a line of conduct which he consistently follows, as fairly harmless. Indeed, he stated, “All great reformers are eccentrics of this kind.”

Eccentricity of a more personal nature, adopted only to draw attention could be problematic. Hammond described a woman who “would have no other material except copper for her table furniture . . . who “carried this fancy to such an extent that even the knives and forks were of copper.” She enjoyed the attention her eccentricity gave her, but she was intelligent and talented in other areas and there seemed no cause for alarm.

Mary Todd Lincoln’s Extravagance and Embarrassing Behavior Earned Her an Insanity Trial

One day she read in a newspaper that “a Mr. Koppermann had arrived at one of the hotels.” She determined to meet him, though her friends tried to talk her out of it. She went to the hotel, was told Koppermann had left for Chicago, bought a rail ticket and started after him. “The telegraph overtook her” Hammond states–whether sent by her or as a warning from her friends–and “she was brought back from Rochester raving for her love of a man she had never seen.” She died of acute mania within a month.

Incidents like the latter could occur due to an inherent tendency surfacing for some reason, but Hammond did not discuss the phenomenon any further.