Dr. Howard W. Haggard

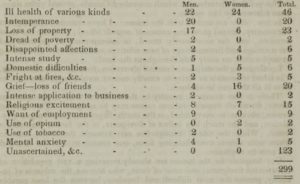

Writing in 1929, Dr. Howard W. Haggard, an associate professor at Yale University, said: “. . . the treatment of mental disease is not so well developed as the treatment of other diseases because insanity has only recently been recognized as a medical problem.” Until shortly before that time, insanity was considered (among other theories) the result of moral failures, harmful actions on the body from outside factors like sunstroke, overwork, a terrifying experience, etc., or heredity weakness.

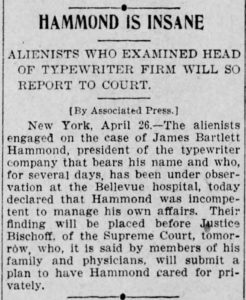

Dr. Haggard also noted that insanity was the only disease that went through a court of law. Though this precaution was presumably taken because the diagnosis could deprive victims of their liberty, Haggard pointed out that a diagnosis of a communicable disease like smallpox could also deprive victims of their freedom through an enforced quarantine. No one required a legal ruling on a smallpox diagnosis, so why the distinction? Haggard believed that insanity had to pass through a court of law primarily because its diagnosis was “not as positive as is the diagnosis for other diseases.”

An Example of Diagnosing Insanity Via the Legal System

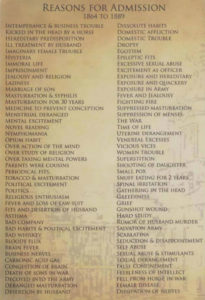

Early Psychiatrists Had Little Idea What Caused Insanity

In this telling statement, Haggard pinpoints the reason we are still arguing today about the validity of diagnosing mental illness. What test is available for a particular mental illness? Whose standards need to be met for a person to be considered free of mental illness? If mental illness is a real condition, why does its definition change over time? A strong sex drive in women used to be considered a form of mental illness, for example, as was epilepsy and syphilis. What currently acceptable behavior will be considered an illness down the road, or what “mental illness” today will science discover is actually a physical illness?

Because these questions cannot be easily answered and have an enormous impact on an individual’s freedom, we as a society will doubtlessly continue the debate for many years.