The Vast Plains Could Be Lonely and Unsettling, photo of Kansas Plains courtesy of U.S. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey

Traumatic events could lead to madness (see last post) for vulnerable individuals, but other, more passive conditions could also affect mental health. Isolation and loneliness caused great distress in even the hardiest pioneers, as seen in cases of prairie madness encountered by homesteaders during the mid to late 1800s.

Away from familiar surroundings and without social support because of the distance between other settlers, victims could fall prey to great despair and hopelessness.This particular syndrome was not an official one, and had a loose set of behaviors that included depression, crying, apathy, and withdrawal, as well as violence and anger. The condition wasn’t even terribly uncommon: E.V. Smalley, the editor of Northwest Illustrated Monthly Magazine, said in 1893, “An alarming amount of insanity occurs in the new prairie States among farmers and their wives.”

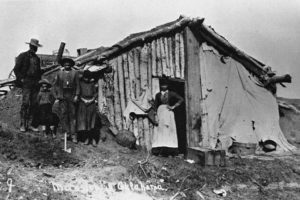

Homesteaders Faced Different Conditions Than They Had in the East

Top issues for many settlers was the move away from home and everything familiar–this issue was even greater for immigrants who came from small, tight-knit villages and spoke a language other than English. The intense hardship of living on the prairie exhausted people physically and made it hard to visualize success. The landscape could be bleak and stretched for miles with no trees to break up the magnitude of isolation, while the wind itself blew constantly and irritated raw nerves beyond coping. Only when the Great Plains became more populated, transportation and communication improved, and towns sprang up, did the condition start to disappear.

A Sod House Was a Far Cry From Most Settlers’ Former Homes, courtesy Library of Congress