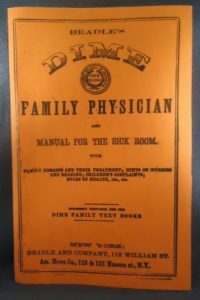

In the 1800s Families Could Be as Medically Informed as Most Doctors

The public originally supported insane asylums because they offered genuine hope. Typical at-home care provided little focused psychological expertise for patients, so recoveries within this family system had been few and far between. (One exception might be for conditions like “melancholia” that could perhaps be treated by a change of scenery.) However, when professionally staffed asylums gave patients the time and attention they needed, recoveries did occur, and the former life-sentence of insanity seemed to have lifted.

John and Thomas Bailey, Father and Son Admitted Simultaneously to an Asylum for Melancholia, courtesy Museum of the Mind

Asylums were imposing, beautifully constructed, and reassuring. Superintendents who had actually been trained in the treatment of insanity–unlike family doctors who may have read a book or two on the topic–added to that reassurance. Families lost their reluctance to send loved ones to asylums and many times were rewarded for their faith. Even those who knew a family member would never recover could at least have the physical and psychological burdens of care lifted from their own shoulders.

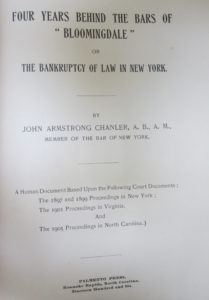

Bloomingdale Asylum Presented a Lovely and Imposing Picture

That first wave of care paved the way for successive waves of continually poorer care as more and more families took advantage of asylums and stretched their resources too thin. At that point, money made all the difference. My next post(s) will discuss some of the differences money made in the quality of care for the insane.