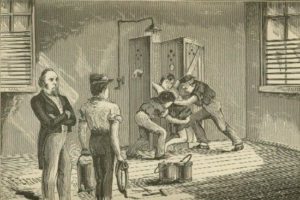

Woman Forced Into Cold Shower, from Elizabeth Packard’s Book Modern Persecution, or Asylums Revealed

Doctors in the asylum era were breaking ground in a new field, and unfortunately, had few scientific studies to reference when it came to treating patients. Most treatments progressed from fairly benign standards like warm or cold baths, enemas, frequent meals, and so on, to more extreme forms of the treatments (baths that lasted hours or days, force feeding, etc.), and then to medicines. Most physicians were quite comfortable–and felt assured of the safety–of medicines that today we know are quite dangerous. Calomel (see last post) is just one example of a favored medicine with dreadful side effects.

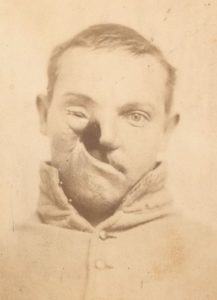

Excited patients–particularly epileptics–might be given bromides to calm them. It worked, but at least one doctor (Chicago physician Dr. J. S. Jewell, writing in an 1881 issue of the New York-based journal The Medical Record) noted that the use of bromides in the treatment of epilepsy actually led to “maniacal furor,” a condition that made the person appear insane.

Skin Eruptions Were Another Side Effect of Bromide Use and Resembled Smallpox, from Materia Medica, 1918

Genetian (which could affect blood pressure and ulcers) was used to stimulate patients’ appetites; hyoscyamia (found in plants like henbane and having an action similar to atropine and belladonna) was used to help patients remain calm or sleep; and ergot ( a fungus which includes a chemical that can cause people eating food contaminated with it to go berserk) was used for “persistent congestion of the brain and cord.”

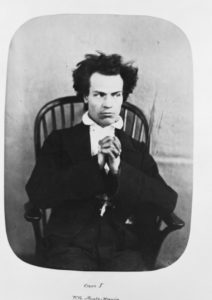

Painting by Matthias Grunewald of Patient Suffering From Advanced Ergot Poisoning, circa 1512

Of course, many medicines used today would be poisonous if they weren’t compounded properly and given in the proper doses. Doctors must also watch for adverse side effects in sensitive individuals and interactions with other drugs patients might be taking. Unfortunately, in the era under discussion, it is unlikely that doctors were skilled at avoiding these potential problems.