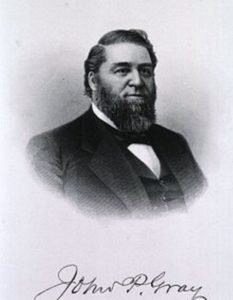

Dr. John P. Gray

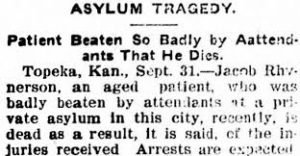

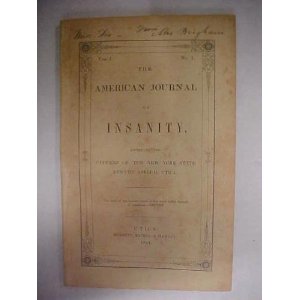

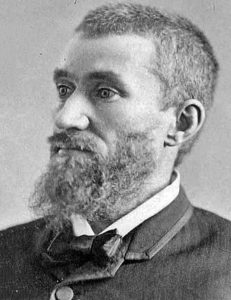

Patients could bear animosity toward asylum staff (see last post), but no one in the public eye was immune from random attack–including Dr. John P. Gray, superintendent of the State Lunatic Asylum in Utica, New York. He had been an expert witness regarding the sanity of Charles J. Guiteau when he stood trial for the assassination of President James Garfield. “I see nothing but a life of moral degradation, moral obliquity, profound selfishness, and disregard for the rights of others,” Gray said [of Guiteau] at trial. “I see no evidence of insanity but simply a life swayed by his own passions.”

The notoriety from this trial likely focused former shoemaker Henry Remshaw’s attention on Gray. Remshaw apparently had made public threats against Gray well before he entered Gray’s office one March evening in 1882 and shot him with a revolver. Fortunately Gray had looked up just at the right moment, and the bullet went through both cheeks rather than his brain. The journal Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of New York reported, “The hemorrhage was at first quite profuse, but in a short time began to subside, and ceased entirely in about four hours. Swelling and infiltration were immediate and extensive, and within a very few minutes of the reception of the wound it was almost impossible to separate the left eyelids, and before midnight the right eye was closed and the face distorted beyond recognition. There was no shock, the pulse ranged between 80 and 90, and the Doctor exhibited perfect self- possession.”

Charles Julius Guiteau

The Transactions of the Medical Society also reported that Remshaw escaped to his brother’s-in-law in the nearby town of Deerfield, “where he called for two glasses of ale and said he was going to New York.” Remshaw later went to the jail and gave himself up. “When searched there was found upon his person four revolvers, a single-barrelled derringer, a dirk knife, and over two hundred cartridges.” Remshaw was sent to the State Asylum for Insane Criminals.

Physicians at the time did not think Gray’s wound particularly serious, but the superintendent never recovered his health entirely. The wound affected his breathing and left him with almost constant pain. Gray died officially of Bright’s disease (which causes inflammation of the kidneys) on November 29, 1886 at the age of 62.

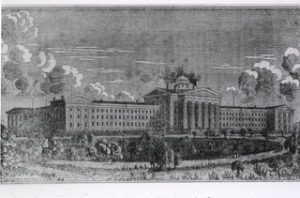

Male Patients Exercising in the Yard of the Utica Psychiatric Hospital, courtesy New York State Archives