A History of Rhode Island

Though insane asylums faced abuse charges after they became overcrowded, they were sanctuaries of peace measured against the care many insane patients had received in city-provided institutions. Cases written about in the book, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History (edited by Edward Field) is probably typical of treatment during the middle-1700s:

Rebecca Gibbs had been under the care of “the Towne of Newport” for 30 years and, “She seemed to be in a sense folded together, her lower limbs being drawn up to her breast so that her knees and her chin met and from this position there was never a change.” A physical deformity would have been bad enough, but Rebecca’s condition was caused by “her having been for several winters shut up in a cell without fire and without clothes, where she had drawn herself as compactly as possible together as a protection against the cold and had so continued till sinew and muscle were unable to relax.”

Thomas R. Hazard Wrote a Ground-Breaking Report on the Treatment of Rhode Island’s Insane in 1851, courtesy Rhode Island Historical Society Library

In a different town, a man was chained and “so wrapped in bagging that when an apple was placed within his reach he could only gnaw it like an animal as it rolled about the floor and he rolled after it.”

Though some towns did treat the insane more kindly, that may have been the exception rather than the rule. Until the new idea of “moral treatment” based on kindness and retraining made its way to America in the 1830s, the insane could not expect comfort or help from society.

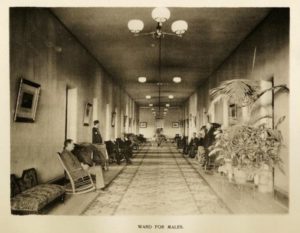

Rhode Island State Hospital for the Insane, Stone Hall, courtesy Rhode Island Department of State