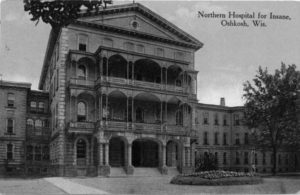

Northern Hospital for the Insane

Though patients were not usually happy to be at an insane asylum, many could still enjoy themselves and have fun under the right circumstances. The Daily Northwestern in Oshkosh, Wisconsin wrote that during one Christmas party, patients enjoyed seeing one of the doctors receive a good-natured gag gift. The patients were delighted with their own gifts, which had been distributed amid festive decorations and a beautiful Christmas tree. However . . .

“Another present worthy of mention was an elegant box of cobwebs received by Dr. Pember who was made the victim of a good joke which many of the patients as well as attendants enjoyed. It appears that the doctor has a great habit of going around the building and upsetting chairs, tables, etc., in search of cobwebs for which it is alleged he has a great abhorrence. As a sort of a take off on his pet pleasure the attendants gathered some cobwebs and gave the doctor a carefully packed box of them,” the paper reported in 1885.

Nurses From Northern Hospital for the Insane, 1890s, courtesy Oshkosh Public Museum

The Daily Northwestern continued: “Messrs. Brightrall, Roberts and Anderson, the gentlemen supervisors, and Misses Mitchell, Schultz and Casey, the lady supervisors, Harry Baum, the druggist, T.J. Vaughn, the steward, Mr. Neville, the warden, Miss Hale, the matron, Dr. Wiggington and his amiable wife and every officer and attendant connected with the institution deserve a deal of credit for the work which they certainly must have done to make the entertainment a success.” The paper added, “One thing is noticeable at the hospital and that is the kindly feeling which all of the patients have for Dr. and Mrs. Wigginton.”

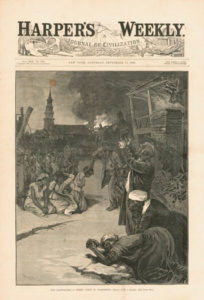

Christmas Decorations at Taunton State Hospital, circa 1900

Though some of this commentary may or may not have been typical hyperbole, various patient memoirs show that patients and staff could indeed develop respect, love, and camaraderie for each other.

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.