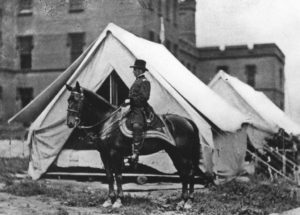

Black Patients Received Less Funding for Mental Health Care, Montevue Asylum in Maryland, circa 1909

Alienists knew that the rates of insanity for various races differed, and came up with several explanations for it. One particularly condescending theory about the lower rates of insanity found in Native Americans and blacks was that these races didn’t face the responsibilities and pressures that so-called “civilized” races did. Especially for blacks, so long as they remained slaves and had most decisions made for them, the theory went, they were relatively untroubled by insanity. With freedom and its burdens, however, came overwhelmed minds that led to mental breakdown.

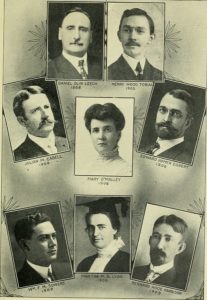

In 1914 Dr. Mary O’Malley at St. Elizabeths’ (Government Hospital for the Insane) compared rates of white and black insanity. What she found initially fit right in with the “civilization” theory: In 1860 during slavery, “one in every 5263 colored persons were insane . . . and in 1910 there was one in every 723 colored persons insane.” O’Malley noted that between 1860 and 1910, insanity in the “colored population” had increased 1,670 per cent.

However, when she studied black and white female* patients–an important distinction–at St. Elizabeths, her results were much less skewed. During the previous four years, 345 black and 455 white women had been admitted. Rates of specific mental conditions proved interesting:

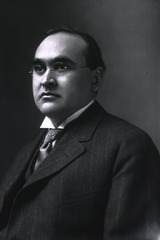

Dr. Mary O’Malley in Center Photograph, photo courtesy of Flickr, taken from History of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia, 1817-1909

Dementia praecox: (black) 37%; (white) 37%

Organic brain disease: (black) 16%; (white)13%

Undifferentiated psychoses (black) 6%; (white) 4%

Manic-depressive: (black) 9%; (white) (11%)

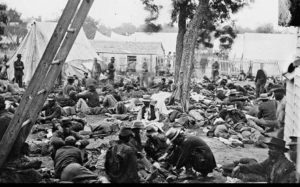

Diversional Occupation at Central Lunatic Asylum in Virginia, the Country’s First Institution for Colored Persons of Unsound Mind

Rates for other diagnoses were similarly close. One distinction that O’Malley did find was that black patients had much lower rates of melancholia and suicidal tendencies. This was especially surprising considering the rates of poverty and lack of status for blacks during this time period.

*Because these women were not veterans as most of St. Elizabeths’ male patients would be–and thus coming from widely differing backgrounds and from many birthplaces–they represented a fairly even-matched pool of impoverished women in the Washington, DC area.