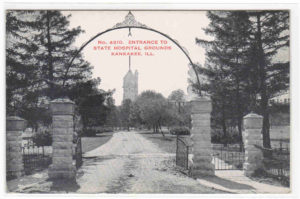

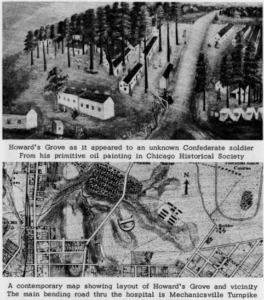

Howard’s Grove Hospital

Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum was the country’s first asylum designated exclusively for the “colored insane.” The institution’s first report explained that the state of Virginia had established the asylum for “colored persons of unsound mind” on the grounds of Howard’s Grove near the city of Richmond.

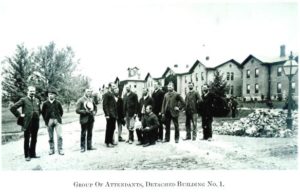

Howard’s Grove Hospital–a former Confederate possession–had been taken over by the Freedman’s Bureau in 1865. The agency used it as a hospital for African-Americans in the area and also for any who wandered in from other places. The Freedman’s Bureau allowed insane patients to stay at the hospital, and in December 1869 the facility was organized as an asylum by order of the military governor of the state, General Canby. At that time, there were 24 males and 45 female patients.

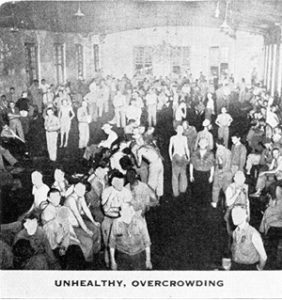

Building for Chronically Ill Females at Central Lunatic Asylum

Virginia took control of the asylum in 1870 and its governor appointed an 11-person court of directors to oversee it; they supported the superintendent’s request for more money to build additional wards in his first report of November 1870. By then, an additional 110 patients had been admitted (December 1869 – November 1870). Eighteen patients had been discharged, fifteen had died, several “idiots” had been sent to alms-houses while a few remained, and altogether 150 persons were in the asylum for treatment on November 1, 1870.

Shenandoah County Alms House, courtesy Shenandoah County Library Archives

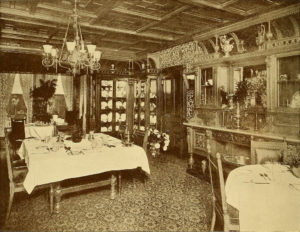

Records on many of the patients were incomplete, but besides “unknown” the two primary causes of admission were “religious excitement” and “congenital idiots and imbeciles.” The two primary forms of mental disease were “chronic mania” and “dementia” with “paroxysmal (temporary) insanity” running a close third.