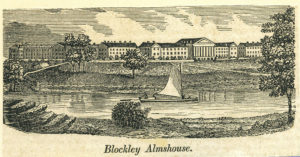

Blockley Alsmhouse

Few patients in mental institutions were so out of touch with reality that their surroundings made no difference to them. One of the pillars of early psychiatric theory was that a patient’s environment did, indeed, made a great deal of difference. This is a particular reason alienists recommended bringing patients out of their old home environments and into the insane asylum’s new one. The implication, of course, was that the asylum’s was better. Most planners did strive to provide stately, serene buildings within a pastoral country setting. The reality did not always match their hopes.

The October, 1876 issue of the American Journal of Insanity included an article by Dr. John Bucknill, “Notes on Asylums for the Insane in America.” In it, Dr. Bucknill pointed out some glaring deficiencies within Philadelphia and New York asylums.

Dr. John Bucknill

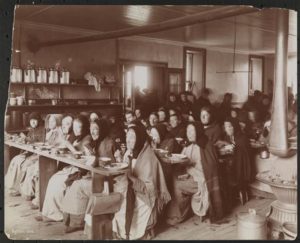

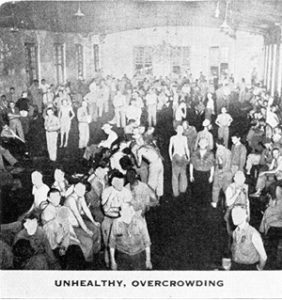

In Philadelphia, a collection of buildings called the Blockley Almshouses, included an insane asylum. The place was constructed to hold 500 patients, and instead held 1,130. Beds were strewn on any available floor space at night to accommodate the extra people, and consequently the air become humid and smelly. Dr. Bucknill noted that there was nowhere for patients to exercise.

The female ward was particularly shameful. In a space designed to accommodate 19 “excited patients” in single rooms, instead held 65 women. The rooms were only six feet by 10 feet to begin with, which was justified by their use to for manic or disturbed patients. Unfortunately, Dr. Bucknill wrote, “. . . these lodging rooms are occupied at night generally by two, and frequently by three persons, and all of them, as I was informed, were regularly put into strait-jackets to prevent mischief during the night.”

Woman Wearing a Strait Jacket in Bed, 1889

How anyone–staff, trustees, inspectors–could have seen this situation and expected patients to recover their sanity says a great deal about the people running it. Dr. Isaac Ray, in an 1873 paper read before the Social Science Association of Philadelphia, said of the conditions: “If homicide is not committed every night of the year, it is certainly not for lack of fitting occasion and opportunity.”