Patients at the Chicago State Hospital walking outdoors on a snow-covered path, Chicago, Illinois, December 10, 1910. The Chicago State Hospital (also called the Dunning Mental Institute) was located at West Irving Park Road and North Narragansett Avenue in the Dunning neighborhood

Insane asylums were dangerous places (see last two posts), since both staff and patients could be the victims of attacks. The balance of power, of course, was always in the staff’s favor, and patients were far more often victims of violence than attendants. Tragically, patients sometimes turned violent against themselves despite all efforts to prevent it:

— Martha Grote suffered from melancholia after the death of a child. She evaded the notice of attendants and took some laudanum from the asylum’s drug closet. No one noticed anything wrong at 9:00 p.m. during the last doctor’s round, but attendants found her almost dead the next morning. They could not revive her. (Cook County Hospital for the Insane, 1897)

— Edward E. McClintock committed suicide by tying one end of the cord of his bathrobe around his neck and fastening the other to a bar on a window in his room. He had suffered from several strokes the last three years “and his brain was affected,” wrote the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey. (Essex County Hospital, 1910)

— James Toovillon had been in the Oregon State Insane Asylum for eighteen years and was considered completely trustworthy . . . but he managed to get hold of strychnine and took his life at the age of 55. (April 7, 1909)

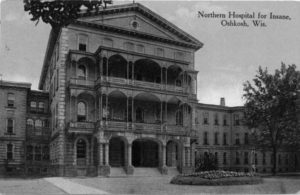

Oregon State Hospital, circa 1900

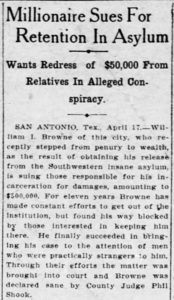

Asylum superintendents despaired over these suicides, and not only because of the negative publicity surrounding them. “It is noteworthy that suicides in asylums occur in streaks,” said Dr. Asa Clark in a newspaper interview in 1905. (Clark was superintendent of the Stockton State Hospital in California.) “One will be followed by two or three others, almost invariably, as these things work upon the minds of other patients.”

That Clark’s belief may have been somewhat true is borne out by a short note in The Tennessean (Nashville) which wrote in 1901 that there was “an epidemic of suicide in [the] asylum for the insane in Shelby County.”

Stockton State Hospital, courtesy California State Library

Clark took what steps he could to keep patients safe and to guard against them learning of other suicides, but he noted that there were “a thousand male patients with but fifty-three attendants.” According to Clark, until the number of attendants increased, it would be impossible to prevent suicides.