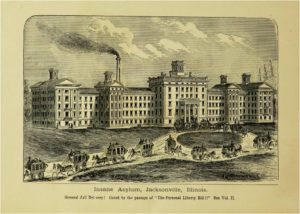

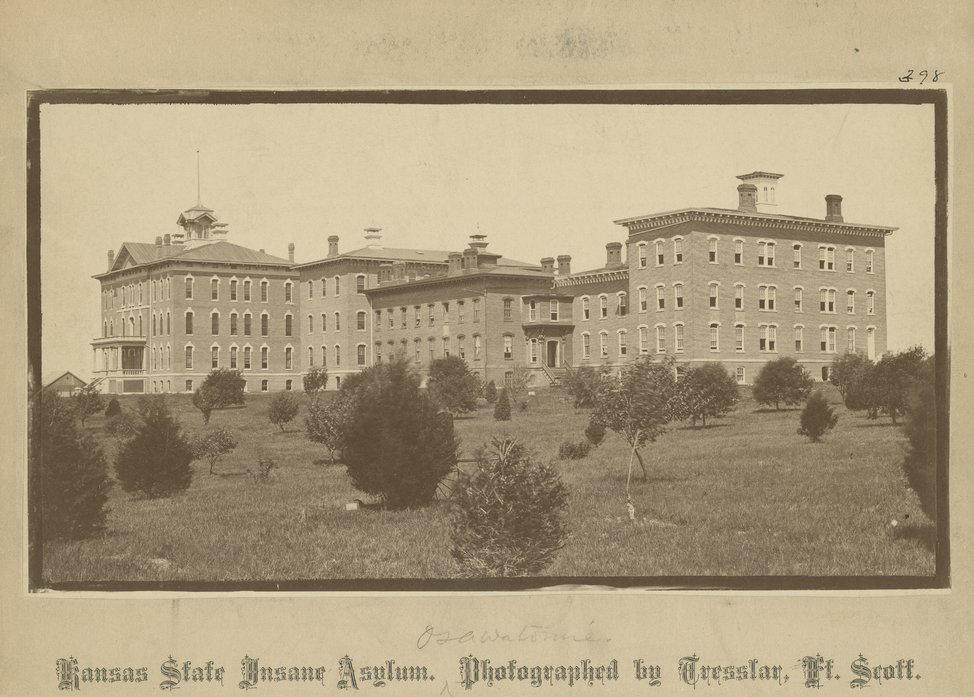

An Early View of the Government Hospital for the Insane

Though Armistice Day (November 11) was renamed Veterans Day only in 1954, veterans with mental health issues did have a special facility to meet their needs quite early on. Though crusader Dorothea Dix had pushed unsuccessfully for federal funding to help pay for America’s (civilian) mentally ill, she and other supporters did manage to get approval for a hospital for the insane of the army, navy, and District of Columbia. On January 15, 1855, the Government Hospital for the Insane received its first patient, Thomas Sessford.

Dr. Charles Nichols was the facility’s first superintendent, and he helped design one of the campus’s earliest buildings, the Center Building. One interesting feature was that the wards used different species of wood for their interiors: the Beech Ward installed woodwork from beeches, and the Cherry and Poplar Wards installed their interior woodwork from like-named trees. The patients had lovely views of the Anacostia River and farmland, and the grounds had extensive trees, shrubs, and flowers to give it a rural feeling of peace.

St. Elizabeths, 1917, courtesy Library of Congress

Allison Building’s Sleeping Porches, 1910, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

The Government Hospital for the Insane became known during the Civil War as St. Elizabeths. Sick soldiers quartered in the hospital were embarrassed to write home from an insane asylum and simply substituted the historic name of the land patent on which the hospital stood. The name was made official in 1916.

My next two posts will discuss early care at St. Elizabeths, and its Civil War operation.

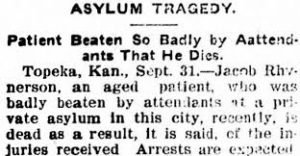

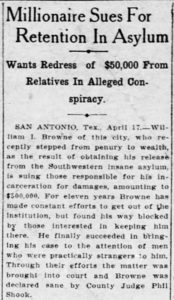

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.

Originally, patients were admitted on a reimbursement plan, either through the county where they lived if impoverished, or through a bond given by their guardians. Private patients paid their own way. Some admissions were voluntary, but otherwise, someone who had been judged incompetent and had an appointed guardian, could be admitted via a jury of six people. One of the six had to be a physician with a regular practice and in good standing. A probate court would determine payment arrangements.