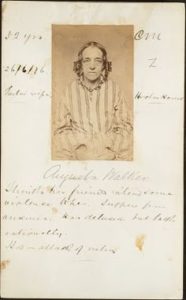

Patient at Bethlem Royal Hospital, aka Bedlam, in a Time Before Moral Treatment

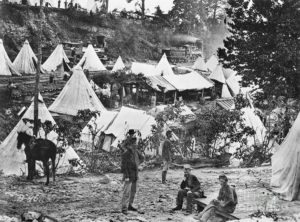

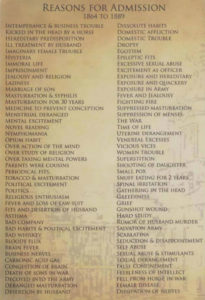

Societies have always recognized mental illness–however they might define it–and early treatments for insanity were usually swift and somewhat brutal. As time went on most governing bodies realized that insane persons were not responsible for their actions; however, they found it difficult to do anything more than house patients somewhere until they either got better or died. These mentally ill people generally lived in harsh conditions at the mercy of their “keepers.” Even after so-called treatments for insanity became available, they remained largely unpleasant: bleeding, whipping, spinning, chaining, isolating from others, etc.

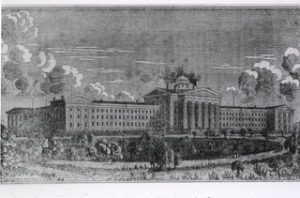

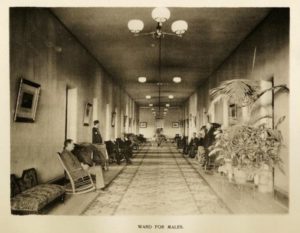

Male Ward at Athens Lunatic Asylum, courtesy Ohio University Libraries, University Archives

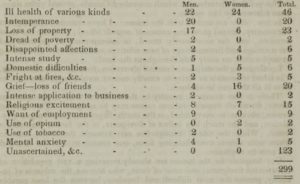

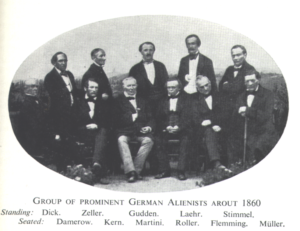

In the early 1800s, reformers such as Dr. Philippe Pinel began to view the insane as people who had lost their reason because of exposure to severe stress or shocks. Victorians had terms like brain fever and shattered nerves to describe this kind of condition. Patients were seen as needing protection from society for a time so they could recover, and many alienists began using fewer restraints and stressful physical treatments. They believed that patients could be helped by moral treatments. These included friendly discussions of the patients’ problems, chores or occupations to discipline their time, and guidance for their interactions with others.

When the public began to see insane people recover, they finally discovered hope for their own loved ones. Asylums became less feared, and even the most reluctant families found them a blessing if a loved one had become violent or too difficult to treat at home. Unfortunately, the public’s embrace of asylums and their modern treatments caused overcrowding. In turn, this led to asylum under-staffing and a deterioration in the staff’s ability to give moral treatment. Soon, patients were merely being “kept” again.