Two Men Cooling Off in a Park During the 1911 New England Heat Wave that Drove Some People to Suicide and Insanity, courtesy New England Historical Society, Library of Congress

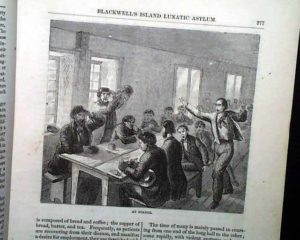

Alienists (early psychiatrists) believed madness could result from a long list of issues such as heredity, strong emotions, sudden shocks, illness, and physical injury. The latter played a part in many patients going to insane asylums, as newspaper accounts and case studies show:

In 1897:

Maggie Mc. —The doctor in the case testified that she can’t be trusted in public, her conduct not being proper. Five years ago she had a fall that left her unconscious for several hours; her wrist was broken at the time, and now there is a suspicion that her skull must have been fractured. The 28-year-old woman was sent to an asylum.

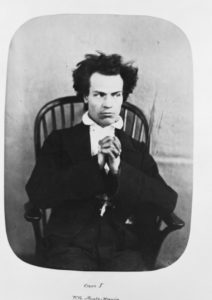

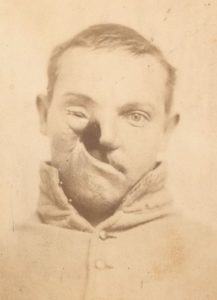

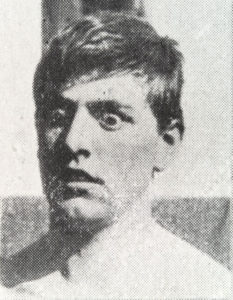

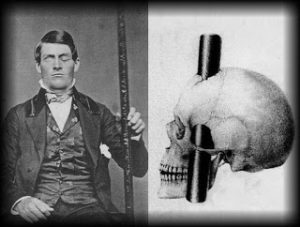

Phineas Gage Underwent a Personality Change After a Tamping Iron Pierced His Skull in 1848

Timothy O’B. — . . . had acquired a big head, ordering dry goods jewelry in great abundance, with no cash to pay; he also imagines he has valuable property. His trouble began by falling from a ladder two years ago and hurting his back and side, and after developing rough behavior, it is said that he was struck over the head by a policeman, through which he has become a raving maniac.

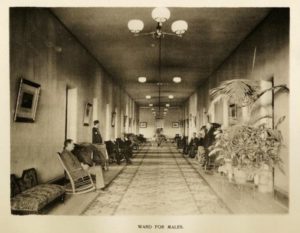

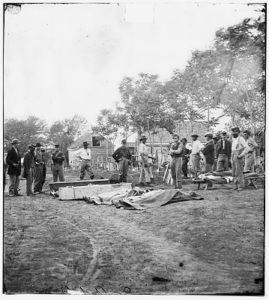

Probable Causes of Insanity Included Injuries, Missouri State Lunatic Asylum, 1854, courtesy Missouri State Archives

Falls from horses, kicks from mules, accidents at work and the like, could all bring on insanity. Most alienists felt that people who did become insane after an injury were predisposed to it anyway, and that the injury brought it out, just as other life experiences like overwork or sudden shock might. An exception would be a traumatic injury to the head which in and of itself could have damaged the brain of an otherwise healthy person.