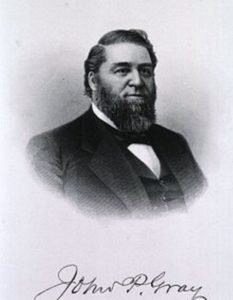

Stephen Smith, State Commissioner of Lunacy in New York, courtesy Appletons Encyclopedia

Most asylum accounts deal with the hardships patients faced, but the employee side had difficulties as well. Dr. Stephen Smith, the State Commissioner of Lunacy in New York, wrote about a particularly difficult type of patient for a paper submitted to the National Conference of Charities and Corrections in 1885. In his “Care of the Filthy Cases of Insanity,” Smith explained the problems caused by this particular “class” of patients.

Filthy patients were those who constantly soiled themselves (whether by accident or design) and required a great deal of any conscientious attendant’s time. In his paper, Smith wrote: “I have seen patients in the asylums of this State who were thoroughly bathed, and had a complete change of under-clothing, and two or three times of their external clothing, eighteen times in a single day. And this occurred in spite of constant watchfulness to anticipate their wants.”

Male patients Being Washed by Hospital Orderlies, courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

Smith encouraged asylums to place filthy patients on a toilet training and personal care program. He also recommended that sufficient staff for a “night service” be employed, their duties being to help with this training program and to ensure messes were promptly cleaned so as not to disturb other patients in the room. When these measures were adopted, Smith had seen wonderful improvements in ward cleanliness, neat and tidy patients, and a much more pleasant atmosphere. Though constant vigilance would have been burdensome, it is still easy to believe attendants would rather have watched these patients closely than clean them up after an accident.

Executive Committee of the National Conference of Charities and Correction, courtesy of the social welfare library, vcu.edu

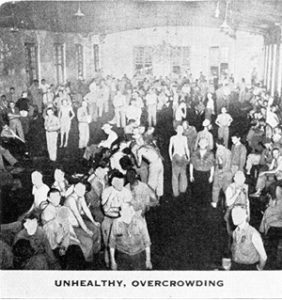

Because many asylums cut their night staffs to provide simple monitoring rather than active care, the financial burden to provide more attendants was likely rejected by most asylums. Day attendants were also stretched thin to save money, but without these measures in place, the stress of time-consuming and unpleasant clean-ups very likely caused more than a few attendants to snap–either at the offender or a handy target.