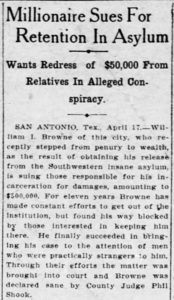

John Taylor, Who Was Committed to Lancaster County Asylum (UK) in 1901 for General Paresis of the Insane

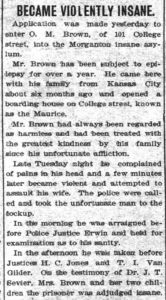

Physical conditions like epilepsy sometimes brought their victims a diagnosis of insanity because of the behaviors these conditions manifested. Other diseases and physical problems were likewise misdiagnosed and forced victims into insane asylums rather than more appropriate hospital treatment. A man described in the October 15, 1870 issue of the British Medical Journal was probably typical. He had been admitted after paranoia and hallucinations made it impossible for him to care for himself. He was only 35 at the time of admission, but had “led an irregular life” for many years prior.

“He said he underwent nightly a kind of torture,which he called the “cylinder finish”, and which he described as an excruciating process, by which his brains were whirled round with extreme velocity, mixed into a pulp, and replaced in his skull just in time for his awaking. This, he believed, was ordered by the doctor, who knew of everything that was done to him, and had the power of regulating the amount of his sufferings,” wrote Dr. H. Grainger Stewart. Commitment to an asylum for a patient like this seemed to make perfect sense.

Al Capone Was Released From Prison in 1939 After a Diagnosis of Syphilis of the Brain

Alienists knew there was little they could do for patients with this form of insanity, called general paralysis of the insane (GPI), beyond giving them sedatives to help them sleep. And sadly, by the time these extreme symptoms manifested, patients often did not have long to live.

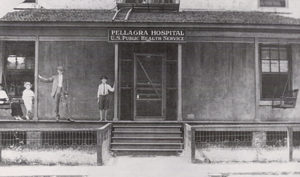

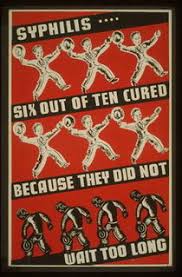

Much of Syphilitic Insanity Could Have Been Prevented With Prompt Treatment for the Initiating Disease

Physicians were able to make a tentative link between GPI and previous exposure to syphilis, but weren’t certain because syphilitic insanity did not respond to treatment with mercury the way syphilis did. However, when the bacterium that caused syphilis was discovered in 1905, a test was developed shortly thereafter to detect its presence. Doctors finally realized that untreated syphilis was the cause of the deteriorating mental condition known as general paralysis (or paresis) of the insane.