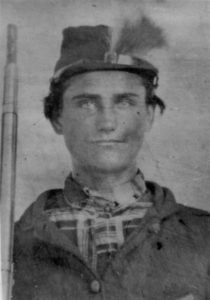

Civil War Soldier Angelo Crapsey, 1861, Who Committed Suicide in 1864 After a Period of Mental Illness, courtesy Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Societies have always observed that participating in wars/battles could affect both the soldiers and civilians caught up in the violence, and not only through physical wounds. After America’s Civil War, people called this change in veterans the “soldier’s heart” phenomenon. At the time, observers believed the negative changes were caused by actual physical changes in the heart that had occurred during war, or that the affected soldiers had longed for home so much that the fixation or focus had affected their minds.

Lunatic asylums had been available to the public for over two decades by the time the Civil War ended, but many families were ashamed to send relatives to them. When soldiers returned from the war, however, families sometimes faced overwhelming problems trying to care for them. If the soldiers were badly wounded, for example, physical care would be demanding and expensive, and mental problems in addition might make giving home-care nearly impossible. Some soldiers returned home with alcohol or morphine dependencies which could also make them difficult to nurse. And, many families–particularly in the South–were too impoverished to provide adequate care for their loved ones.

Milledgeville Lunatic Asylum, GA, Received its First Patient in 1842

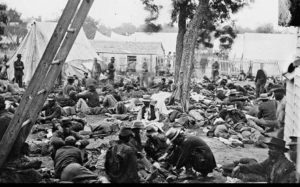

Some of these issues may have driven families to place their veterans in an asylum. At the time, treatments for the insane consisted primarily of rest, occupational therapy, and adequate care for any existing physical problems. Receiving these things would have helped many patients, as would the relative peace that came from the stability and routine found in an asylum. Little besides some light labor and observance of the rules would have been expected from these patients, and many soldiers possibly welcomed the change and the chance to rest from the uncertainty and stress of the battlefield. Asylum cure rates during this period after the war could be around 30 to 40 percent–high, but possibly accurate.

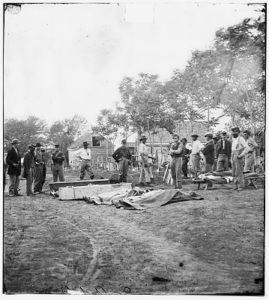

Soldiers Could Be Traumatized When They Saw Friends and Comrades Die, photo courtesy Library of Congress, 1861

Though many families continued to resist asylums and could not get beyond the stigma of insanity, others who used the asylums possibly saw a benefit. At the very least, many families may have felt that under post-war circumstances, they could have provided no better care, themselves.