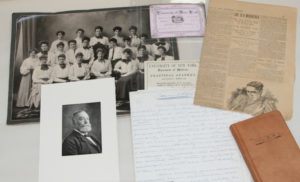

Collection of Dr. Alexander E. MacDonald’s Papers, courtesy New York Academy of Medicine

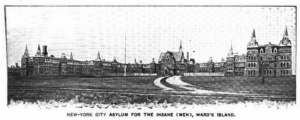

In 1874 Dr. Alexander E. MacDonald accepted an appointment as superintendent for Ward’s Island’s insane asylum. Conditions there were dreadful (see last two posts) and MacDonald requested a new wing to the main building in 1878 to relieve some of the chronic overcrowding. Both patients and convicts worked on the new construction–not necessarily unusual for the period.

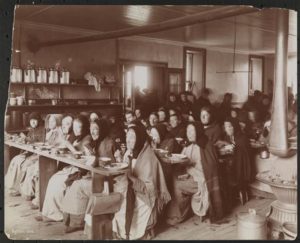

Cheapness had prevailed since day one, and professionals believed that many of the asylum’s cases became chronic because they had not been helped adequately from the start. Even meals were excessively frugal: “Dry bread was a staple article of diet, few accompaniments were permitted and much was diverted by the so-called “cook,” who was selected from the workhouse prisoners,” wrote one of the doctors compiling a history of New York asylums. His assessment is underscored by the fact that when an additional five cents was added to the dietary allowance, along with an improvement in cooking, more patients recovered.

A Supper of Bread, Butter, and Tea on Blackwell’s Island, from an 1866 Illustration in Harper’s Weekly

Dr. MacDonald also improved patients’ clothing, bedding, and ward furniture and he fought for a “more liberal” amusement fund to help divert patients’ minds from their problems and give them some enjoyment during their stay. He also fought for attendants, saying that “$20 a month with board was too small compensation for 15 hours [a day] spent in the companionship of the insane.” He called for a whopping 50% increase in pay to $30 a month. Along with this, MacDonald protested using convicts as attendants and managed to get at least the female ones withdrawn. By 1880 he had stopped the use of restraints like manacles, wristlets, and seclusion.

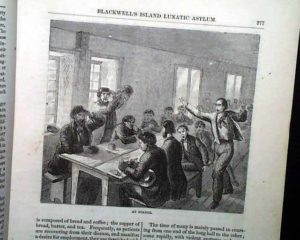

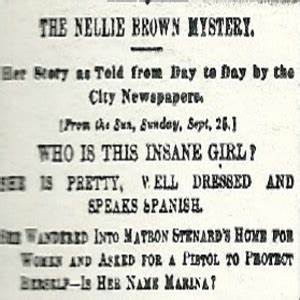

Nellie Bly Posed as an Insane Woman for Her Exposé

Though MacDonald tried with probably the best will in the world, the four institutions in the Manhattan region were often investigated for a variety of failures. Nellie Bly’s exposé in 1887 is probably the best-known, though many other scandals made it into public knowledge.