Thomas Nast’s Picture of a Homesick Soldier

America’s Civil War left many soldiers with lingering mental ailments that degraded their quality of life or disrupted it so violently they were considered insane. Today we would likely call these problems post-traumatic stress disorder, but in the 19th century it would have been called soldier’s heart or irritable heart.

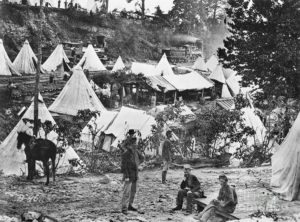

Another syndrome that affected soldiers during the war was called nostalgia. Men (and boys) who had never traveled far from home were suddenly in a strange place away from family and friends. Many were so homesick that they fell into depression and despair, stopped responding to the people and stimuli around them, and sometimes became so lethargic and apathetic that they died.

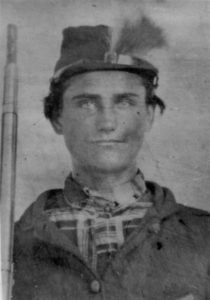

John Clem, a 12-Year-Old Union Drummer Boy, Would Surely Have Had a Hard Time Coping With Homesickness

Nostalgia was recognized in the 1863 Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers. The manual said: “Nostalgia is a form of mental disease which comes more frequently under the observation of the military surgeon… it belongs to the class Melancholia.”

The typical camp treatment for nostalgia was to shame soldiers for it, increase their drilling and other training, or push them into combat to stimulate them. Letting them take leave, or furlough, was also an option, but camp physicians had little use for it. Many were more concerned about the physically ill and wounded–whose symptoms could not be faked–than they were with uninjured soldiers who had symptoms that could.

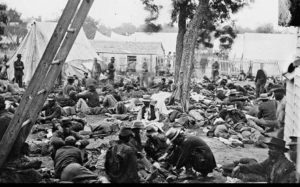

It Would Have Been Impossible to Treat Nostalgia in a Civil War Hospital Like This

This cold attitude was driven more by the wartime situation than the prevailing attitude of the era. Moral treatment, with its kinder outlook and sympathetic treatment of the mentally ill still dominated treatment in asylums. Unfortunately, the Civil War demanded soldiers so relentlessly that physicians found it hard to justify releasing a relatively able-bodied soldier from the army, for any reason.

Nostalgia was a very old term for the illness it represented, and the Civil War was the last war in which Americans used it as a diagnosis.