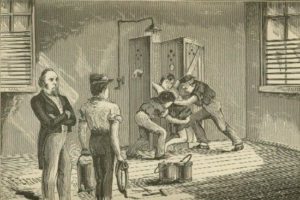

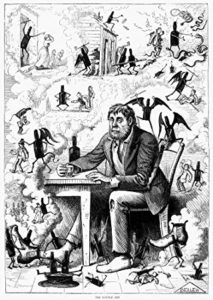

A Temperance Poster by Frank Bellew, 1874

In the 19th-century mind, excessive use of or dependency on alcohol was closely related to insanity. Dr. Hills, superintendent of the Central Ohio Lunatic Asylum wrote in 1888, “Intemperance is a frequent direct cause of insanity . . . but many instances come to light in which even temporary intemperance in the parent has caused constitutional defects in the offspring–sometimes physical and at other times mental.”

Hills went on to relate a case in which a father with six sons had been a hard drinker in his earlier years. One son was born with a dull intellect, another went insane at age 30 “and is probably incurable” the third “was demented from an early age,” and the fourth was epileptic and “is imbecile.” Two older sons were married and had children, said Hills, “some of whom can hardly hope to escape the penalty in after years.”

Americans imbibed huge quantities of liquor beginning with colonial times, but frowned on public drunkenness. In general, society considered excessive drinking a sin and a moral failure. Eventually medical men (and others) began to look on alcoholism in a different way. Many could not keep from feeling that because drinking was voluntary it had to be a related to morals, but eventually people came to take a more hybrid view that it was a moral failing that led to a physical condition that couldn’t be controlled.

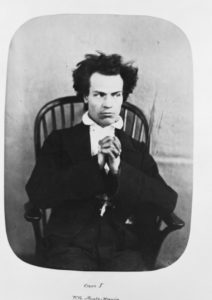

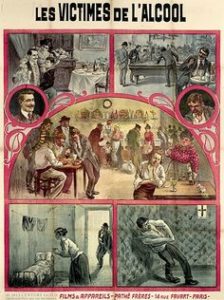

The Victims of Alcohol, Film Poster, 1911

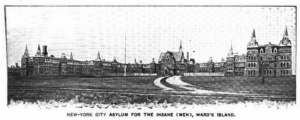

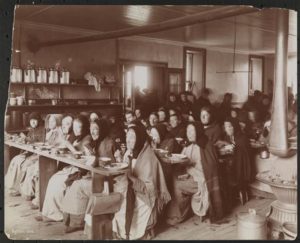

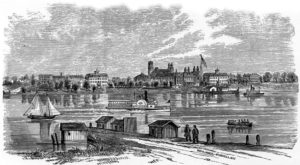

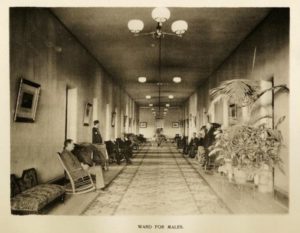

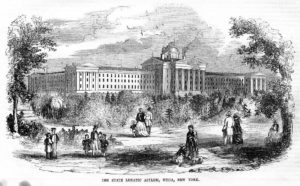

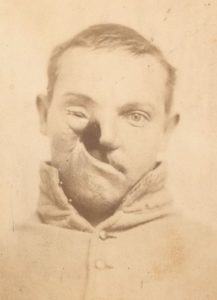

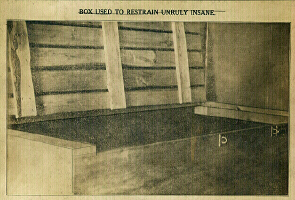

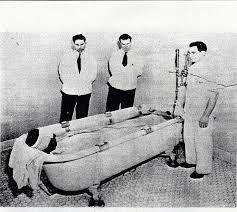

People who became alcoholics or met with public attention during a binge were often sent to insane asylums and diagnosed with “alcoholic insanity.” Reformers began to call for separate inebriate asylums where people with alcohol problems could be helped in a deliberate way. They could make the same arguments that had been made for treatment in asylums: it was cheaper to cure a man than for the public to absorb a lifetime of costs associated with drunkenness; medical staff could provide better care than family members could; alcoholics could be watched at all times and intoxicating drinks kept out of their hands, and so on.

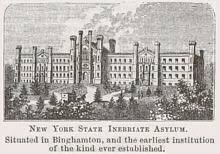

New York State Inebriate Asylum

As with the insane, alcoholics could be committed to an asylum against their will. It took affidavits from two physicians and two “respectable citizens” that the person in question was lost to self-control, unable to attend to business, or “dangerous to remain at large,” to send that person before a judge for determination. For the New York State Inebriate Asylum, there was at least one safeguard: An involuntary commitment could not be for longer than one year.