Sidis Psychotherapeutic Institute, courtesy Sidis Archives

Early asylum care was dramatically better than what families could provide at home (see last post), but institutional care began to fail once asylums became popular enough to be overcrowded. Legislators were aghast at the public’s demand for more admissions, which consequently meant more available rooms, buildings, staff–and public funding. State governments typically met this challenge by insisting that asylums make their money go further, which often meant skimping on amenities and staff.

Dining Room at Sidis Psychotherapeutic Institute

This didn’t need to happen at private establishments where patients could pay for the level of care they wanted, or for private-pay patients at public institutions. Boris Sidis, who opened his private institution, the Sidis Psychotherapeutic Institute in New Hampshire in 1910, knew to emphasize the luxurious accommodations available. “Palatial rooms, luxuriously furnished private baths, green houses, sun parlors, and private farm products” were just some of the amenities sure to delight his patients and set their families’ minds at rest.

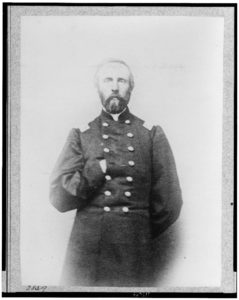

Boris Sidis, courtesy Atlantic Monthly, 1922

Sidis charged between what would be (in today’s dollars) $1,000 – $2,000 a week for his services. One can only imagine how nice life could have been there, and what a pleasant retreat his institute was for patients who went there voluntarily, as many did.