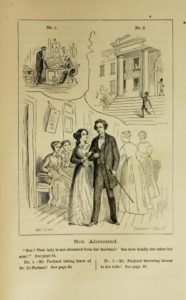

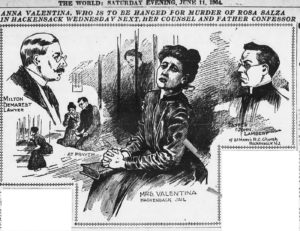

Anna Faced an Unsympathetic Judge

After being ill-used by her partner for years, Anna Valentina went temporarily insane and killed her lover’s new mistress (see last post) on March 10, 1904. The judge did not even consider an insanity plea, and Anna was duly sentenced to be hanged on May 12, 1905. However, a newspaper article and an outpouring of public sympathy spurred many efforts to either win a pardon for her or secure imprisonment instead of hanging. Even the prosecutor in the case said on appeal that though evidence demanded a guilty verdict, many people on the jury may have felt Anna would be pardoned and did not fight it.

Despite her supporter’s best efforts, an article in the May 5, 1905 Camden Courier-Post stated: “[The] Court of Pardons refused this afternoon to interfere in the case of Anna Valentine, sentenced to be hanged May 12 in Bergen.”

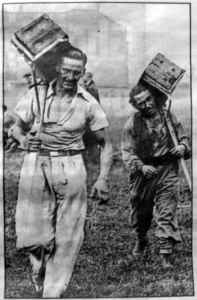

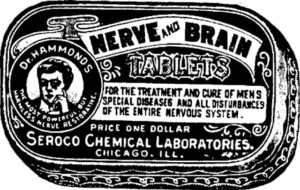

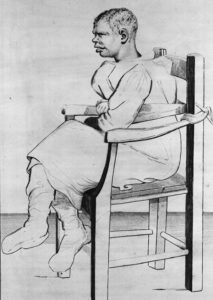

Gruesome Rendition of Preparations for Anna’s Execution

The case went to New Jersey’s Supreme Court, but was met without sympathy. Justice Garretson re-sentenced Anna to death, and the newspaper reporting it noted this time that Anna had stabbed her victim 17 times while the woman was holding a baby. Though the frenzy of the stabbing might have made the case that Anna had completely lost control, the judicial system did not consider it.

Anna On Her Way to Prison In Her New Hat

Public sympathy would not be stilled, however, and both private citizens and organizations fought for clemency in the case. Anna received a stay of execution only a few days before she was supposed to hang, but eventually the judge set a new date for January, 1906. The hanging was further delayed until May 25, but finally, on May 17, 1906, Anna’s execution was commuted to life in prison. The sheriff’s wife bought Anna a new hat to wear on her trip to her new home.