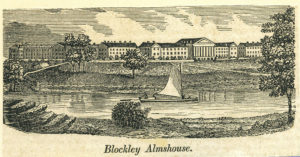

Illustration Showing a Black Man Sitting in a Chair Wearing a Straitjacket, courtesy National Library of Medicine

When British physician Dr. John Bucknill visited U.S. insane asylums and wrote an article about his observations for the October, 1876 edition of the American Journal of Insanity (see last post), he discussed the issue of restraining patients. British asylums had done away with restraints almost entirely, and Bucknill did not like to see them used as freely in the U.S. as he saw during his visits. In his discussion about their use in America, he made the following observations:

Dr. Green of the Georgia State Asylum said that he did not like to use restraints, but did with four classes of patients. These were: suicidal patients, persons who will not remain in bed, persons who persistently denude themselves of all clothing, and inveterate masturbators.

Bucknill also mentioned that Dr. Ranney, who prided McLean Asylum with bringing its use of restraints down to a very low level, still used mechanical restraints on the following types of patients: those exhibiting acute mania; patients who wound themselves, creating ulcers that would never heal themselves unless their hands were confined; epileptic patients who so often became violent; persons whose feelings are greatly perverted and prone to see insults or evidence of conspiracy, who were sometimes little less ferocious than wild beasts; and persons in the throes of acute delirious mania.

McLean Asylum, courtesy Boston Public Library, Digital Commonwealth

“It will be observed,” said Dr. Bucknill, “that . . . we already have nine classes of lunatics who need mechanical restraint, in America.” He added that Dr. Slusser of the Ohio Hospital for the Insane added another class: “. . . those who persistently walk or stand, until their extremities become swollen, and they give evident signs of physical prostration. I have no way of controlling such, but by tying them down on a seat.”

This addition made ten classes of patients needing restraint, but Dr. Bucknill continued with a list of other reasons doctors restrained their patients until he named “fourteen classes of the insane altogether who absolutely need mechanical restraint in the State Asylums of America.” Bucknill noted some ways that British asylums found to avoid restraints, but realized that the American mindset was simply different on this issue.

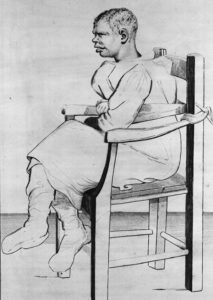

Mock-up of a Patient in a Restraining Device Called a Utica Crib

Bucknill did say, “Is it surprising that, at the present time, the management of asylums for the insane in America is the subject of mistrust with the people?”