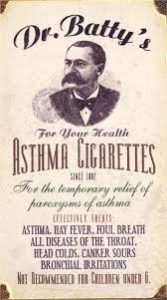

Medicine for Asthma Went Straight to the Lungs Via Cigarettes

Many nineteenth-century theories about disease and mental illness were based on assumptions that made sense within the limited knowledge of the time. Unfortunately, quacks could pick up on ill-founded theories and make a fortune if they were good salespeople–and of course, most were excellent. Dr. Edwin Hartley Pratt’s theory about chronic disease resulting from irritation of bodily orifices (see last post) is a case in point.

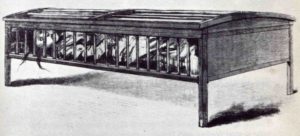

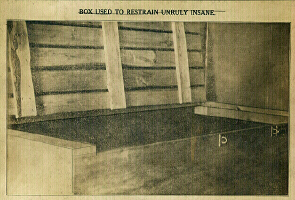

Dr. Frank E. Young took on the orifice problem and created rectal dilators with exaggerated claims: they were good for anemia, constipation, sallow skin, acne, insomnia, anorexia, headaches, and on and on. These rubber plugs–shaped somewhat like a torpedo–also cured insanity. In promoting his cure, Young asserted, “three-fourths of all the howling maniacs of the world” were curable “in a few weeks’ time by the application of orificial methods.”*

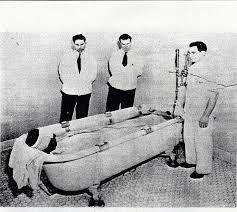

Dr. Young’s Rectal Dilators

Though the medical world scoffed, Young’s devices were popular (primarily for constipation) until the FDA began to regulate and oversee medical devices in 1938. In 1940 the agency seized a shipment of Young’s dilators as misbranded (because of their claims to cure so many conditions) and Young’s company fell out of favor.

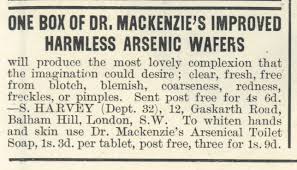

Arsenic for Beauty Typified the Errors in 1800s Medical Knowledge

*Reported in The Medical News, April 29, 1893, p. 471.