Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1866, Showed A Doctor Making His Rounds at Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum

The attendants working in insane asylums often had deservedly poor reputations. However, many were dedicated and capable, and performed their duties admirably. We can only imagine the outcome of any number of harrowing situations if attendants had not remained calm and committed to the people who depended on them.

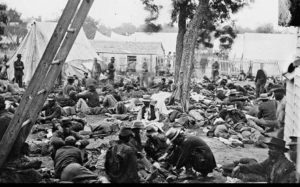

An article in an 1879 issue of the New York Times reported on a fire that had broken out in a large building beside the main asylum on Blackwell’s Island. The building held about 100 female patients, who were locked in rows of cells on each floor. Smoke began pouring out of the cellar late in the evening and attendants gave the alarm. The Medical Superintendent had them unlock each cell and release the patients, but getting them outside to safety could have been quite a task given the unusual circumstances and mental state of the patients.

An Asylum Dance at Blackwell’s Island

However, to calm patients’ fear and excitement, the attendants told the women “there was to be a dance in the Amusement Hall, a building in which concerts and balls were given to the inmates of the asylum,” the paper reported.

The patients exited via fire escapes, and to keep up the pretense that all was well, someone played “a merry air” on the piano in the Amusement Hall. Some of the patients began to dance on the lawn as employees and others fought the fire, and every life was saved.

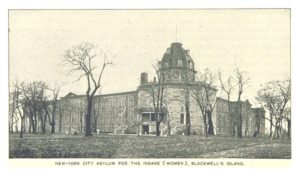

New York City Asylum for the Insane on Blackwell’s Island