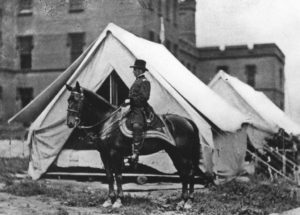

General Joseph Hooker Received Care at St. Elizabeths, courtesy NARA RG 418-P-717

Before the Civil War began, Dr. Nichols (see last two posts) and his oversight committee decided to open up the unfinished east wing of the asylum to the army’s use for sick soldiers. The space was officially called St. Elizabeth Army General Hospital, but soldiers called it St. Elizabeths when they wrote home. Nichols also opened a building called the West Lodge to the navy.

Nichols was hard pressed to run the asylum and help the military side of the operation as well. For the most part, only the military’s sick came to the hospital, though a few hundred (out of about 1,900) patients were treated for war wounds. In April 1863, however, military hospitals began to send their patients with amputated legs to St. Elizabeths because it had opened up a prosthetic limb shop. Soldiers with leg amputations received surgical treatment there, were fitted for legs, and remained until healed. The patient also learned how to clean and oil his new leg and care for it under the supervision of R. W. Jewett, who had patented the artificial limb shop.

St. Elizabeths’ Civil War Cemetery, circa 1897

Many inconveniences resulted from the asylum’s accommodation of the military, including prime agricultural land being taken from service for ordnance training. Nichols also found it hard to collect from paying patients whose families lived in the South. (Out of compassion, he did not discharge these patients.) Foraging soldiers stole food from the hospital’s garden, and numerous other trespasses–like stealing coal–frustrated Nichols repeatedly.

The Army Maintained Many Hospitals During the Civil War. This is Ward K of Armory Square Hospital, Washington, DC, 1862, Located Approximately Where the National Air and Space Museum Stands Today, courtesy Library of Congress

As the war went on, 85 percent of the total number of admissions to the asylum came from the army. The rate of navy admissions was much lower because in Nichols’ words: “. . . the seaman has a more hardy and unsusceptible [sic] constitution than the landsman.”