Main Street in Norman, OK, 1889, courtesy Emma Coleman Photography Collection, University of Oklahoma

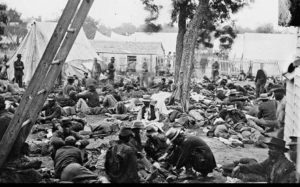

Several states had created insane asylums while they were still part of a Territory; Oklahoma was one of these. The Cherokee Nation actually established the first asylum in the area when they erected the Cherokee Home for the Insane, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind outside the city of Tahlequah in 1873.

The Territory’s non-native insane were sent to Jacksonville, Illinois for treatment until two physicians created a private company called the Oklahoma Sanitarium Company. The Territorial Legislation awarded them a three-year contract to care for the insane, hoping to cut down on transportation costs for patients going to Illinois. The company constructed a hospital (the Oklahoma State Hospital) at Norman, OK in 1895. The Territory also approved a second asylum (Oklahoma Hospital for the Insane) in Supply, OK in 1905.

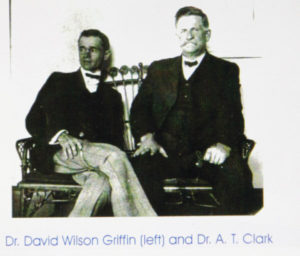

Dr. Griffin Was Hired from North Carolina in 1899 and Became Superintendent in 1902

Because Oklahoma’s institutions were created later on in the asylum era (a third one opened in 1913), care was relatively modern: the State Hospital’s staff consisted of both attendants and nurses, as well as a physician-superintendent and assistant physicians. By 1910, it had even adopted the practice of employing women nurses in male wards. Within twenty years of its creation, the hospital had a training school for nurses and a laboratory.

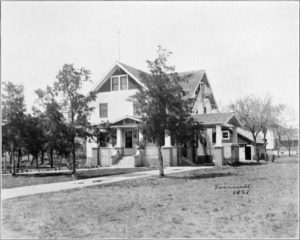

Oklahoma Sanitarium Building, 1897, courtesy Emma Coleman Photography Collection, Oklahoma University

A 1909 report from the institution shows that 94 patients were either released or “restored” and 48 released as “improved.” A number of other patients (71) were paroled, that is, given the opportunity to go home to see how they would do, while 15 managed to escape.

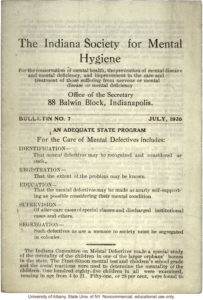

For those in the asylum at the time, a majority diagnosis was hereditary insanity. Other causes for insanity included: ill health; syphilis; inebriates; old age; drugs; child birth; mental worry; privation; injury to brain; epilepsy; sunstroke; pellagra; and self abuse.