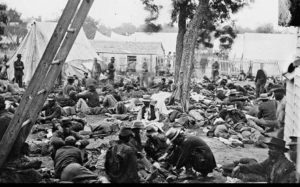

Bloomingdale Asylum

Patients were often kept in insane asylums far too long because they were friendless or without family to take them in, even after improvement. Wealthier patients could fare better since it was easier for their families to hire attendants for home care, but wealth did not guarantee their welcome back into the family circle.

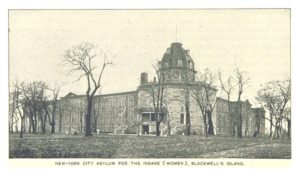

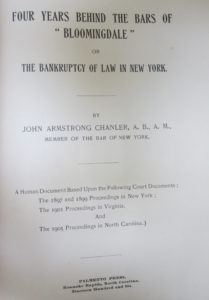

Millionaire John Armstrong Chanler’s family (part of the wealthy Astor clan) committed him to an asylum probably to prevent him carrying out business plans they thought were risky. He was a resident of Virginia, but was tricked by a friend into going to New York City. There, he was subsequently committed to New York Hospital, also called Bloomingdale Asylum. His family promptly cut him out of their lives.

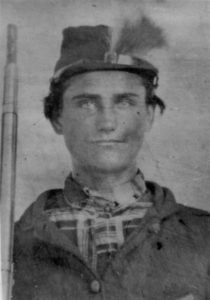

Chanler seated on a horse, 1912, courtesy Holsinger Studio Collection and U.Va. Digitization Services

Unfortunately for them, Chanler managed to write an impassioned plea for help and smuggle it out of Bloomingdale via a discharged journalist who had been committed for morphine addiction. The reporter didn’t get the letter to Chanler’s lawyer, but instead wrote a sensational story. Though the story publicized his plight, little help resulted.

Chanler’s Scathing Report on His Stay at Bloomingdale

Chanler trained himself to walk far and fast, and on Thanksgiving Eve, 1900, he slipped out the gates of Bloomingdale, perhaps with the help of a loyal friend. Chanler made it back to Virginia where his friends helped him pursue a trial to determine his state of mind. The ultimate result: Chanler was declared legally sane in that state. Years later, the New York courts also found him sane.

This is one instance–a rarity indeed–of triumph for someone whose family had been determined to keep him in an asylum.