Young Theodore Roosevelt

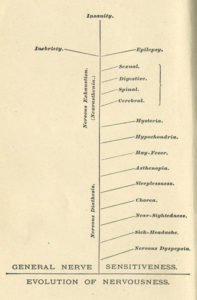

“Nervous disease” or more generally, neurasthenia (see last post), was a uniquely American disease of the 20th century. It affected mainly high achievers and the wealthy who exhausted themselves by the stress of their pursuits.

Teddy Roosevelt (born in 1858) was from a wealthy family whose mother could not cope with domestic responsibilities and developed neurasthenia. Roosevelt himself was a sickly child who managed to heal through a rigorous exercise program that included boxing. However, his father’s death gave him an emotional and mental blow that was hard to overcome. Roosevelt became depressed, endured drastic mood swings, and fell into heavy drinking at college; he recovered after falling in love with and marrying Alice Hathaway Lee. However, on February 14, 1883, both his wife and his mother died within a few hours of each other.

Roosevelt as a Cowboy in Dakota Territory, courtesy Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

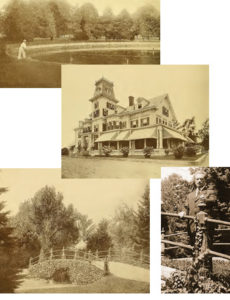

Only 25, Roosevelt was devastated and again developed symptoms of neurasthenia. Physician Silas Weir Mitchell typically put women to bed for a rest cure when they developed neurasthenia, but he sent men to the West where they could rope cattle, hunt, explore rugged terrain and ride horses. Roosevelt followed Weir’s protocol and went to Dakota Territory, spending the next two years working cattle and working as a sheriff.

Col. Theodore Roosevelt, of the Rough Riders, 1898, courtesy Underwood & Underwood

Roosevelt’s encounters with cattle thieves and lawless gangs–along with developing the skills needed to break and ride wild horses–changed both his body and mental condition. When he returned East, he married his childhood sweetheart and became the politician and conservationist remembered today. Roosevelt considered physical exercise so important to his well-being that he even brought in a professional sparring partner so he could box at the White House after becoming president.